From his seat behind the team bench, Ryan Lumpkin, a 26-year-old player development coach for the Wizards, could feel the eyeballs bearing down on him. It was last October, in the season opener, and Washington star Bradley Beal was whistled for a foul following a collision with Toronto’s OG Anunoby. Lumpkin could feel his heart rate spiking. “My Apple Watch,” he says, “was telling me something was up.”

Matt Reynolds knows the feeling. In the second quarter of Game 3 of Boston’s conference semifinals series against Milwaukee, Reynolds, a Celtics assistant, watched as a referee signaled a block on Marcus Smart—a call that, if it had gone the other way, would have meant the third foul on the Bucks star Giannis Antetokounmpo. Charles Klask, a Nuggets assistant, winces when he recalls a regular-season game against the 76erswhen JaMychal Green rushed toward him, finger twirling—the universal sign to call for a coach’s challenge—because a reversal would mean a fourth foul for Joel Embiid. “Some of these are game-changing moments,” says Klask. “All you’re thinking is, I better get this right.”

The coach’s challenge landed in the NBA rule book on a trial basis in 2019, and then permanently a year later. Inspired by the success of the NFL’s version, NBA coaches pushed for it and, after five years of experimentation in the G League, won the right to use it. While it’s the head coach who signals for a review—that familiar finger twirl that triggers a neon-green light at the scorer’s table that leads to a trio of referees huddling around a monitor—each has someone they lean on. They are, simply, the challenge guys, anonymous assistants, unless your gaze happens upon a backbencher with his head buried in his laptop. They are the people you (unwittingly) cheer when a missed call gets overturned, the ones you (unknowingly) curse when a team refuses to challenge one. When an entire bench swivels on a close play, they are the midlevel staffers in polo shirts everyone is staring at. “Think of them like the long snapper,” says Raptors coach Nick Nurse. “Nobody knows who they are until they hike it over the quarterback’s head.”

Challenge coaches aren’t selected as much as drafted. Shortly after the NBA approved the challenge, Reynolds, then Boston’s video coordinator, received a text from then Celtics coach Brad Stevens. “You have to become an expert in the rules,” the message read. Dylan Murphy, a sports radio intern turned G League assistant, hooked on to Steve Clifford’s Magic staff in 2018. He was thrust into the role and immediately devoured the rule book. “There are so many random details,” says Murphy, who is still with Orlando. “I had to memorize it.” Jordan Sears, the Mavericks’ video coordinator, says he was “kind of roped into it”—in part, he says, because of his calm demeanor. “I knew it would be a stressful job,” says Sears. “But I didn’t realize how much of a hot seat it is.”

For the challenge guy, the job begins before the whistle. “You’re always logging things,” says Klask. “Do we have timeouts? What are the players’ foul situations? Would the challenge lead to our possession or a jump ball? Could it take away points from the board?” After the whistle blows, every moment is precious. “Usually you have about 10 seconds,” says Reynolds. “Twenty, max.” From a laptop, coaches have access to multiple feeds. There is the arena house video, called the coach’s camera, which each team can view. There are home and visiting TV broadcasts. “Sometimes there is a lag of three to five seconds,” says Klask. “And it’s the longest three to five seconds of your life.” Team broadcasts, which will quickly cut to replays of a close call, often from multiple angles, can be useful. “In theory,” says Reynolds, “you have access to slow-motion replay”—but it’s at the whim of a director. For some challenge guys, an iPad, on which a pinch of the fingers allows them to zoom in, is an asset. But most prefer the larger screens—and the ability to cram in multiple views in different windows—afforded by laptops.

There’s gamesmanship with challenges. Several coaches say game operations staff are instructed to get replays of questionable calls against the home team up on the jumbotron quickly. Conversely, when an iffy call goes against the road team, game ops are asked not to show a replay at all.

Teams have one challenge per game and, unlike in the NFL, if a call is overturned, a team does not get the challenge back. “Our philosophy is to use it in high-leverage situations,” says Nathan Bubes, a Timberwolves assistant. Foul trouble, for example. Last spring, in Game 5 of Minnesota’s first-round series against Memphis, Karl-Anthony Towns was called for a charge after barreling into Jaren Jackson Jr. in the third quarter. In general, T-Wolves coach Chris Finch prefers to hold on to his challenge until the fourth quarter. But the whistle was the fourth foul on Towns. Minnesota reviewed it, won and instead Jackson picked up his fourth foul and headed to the bench.

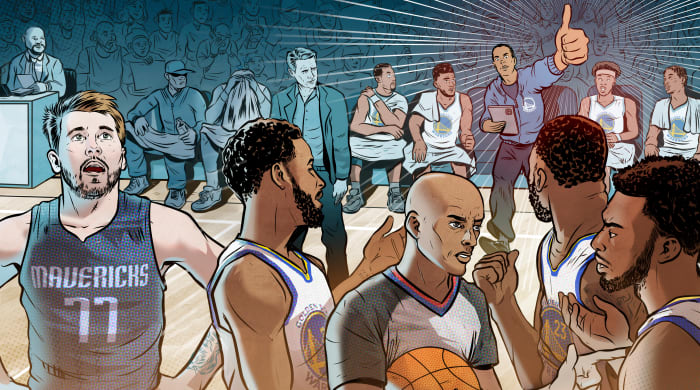

Golden State, similarly, likes to have its challenge available in the final minutes. Sometimes, says Warriors assistant Jama Mahlalela, there are “situational choices.” In Game 3 of the conference finals against Dallas, Andrew Wiggins was called for a charge after an acrobatic dunk on Luka Doncic midway through the fourth. “It didn’t quite fit our parameters for when to challenge,” says Mahlalela. But the moment—the dunk energized the team and gave the Warriors a 10-point lead—called for it. “I really didn’t know if we’d win it or not,” says Mahlalela. “But everything in that moment felt like we should try.” The challenge was successful; Golden State would win the game by nine.

Head coaches tell challenge guys: Be decisive. “Steve [Kerr] wants me to be clear,” says Mahlalela. “Thumbs up, challenge it. Thumbs down, don’t. He doesn’t really want anything else.” Adds Murphy, “It doesn’t help if everyone turns around and you’re like, ‘I don’t know, maybe?’ “

Certain calls are easy. Coaches had a 74.7% success rate on out-of-bounds challenges last season. For goaltending, it was 78.6%. Most calls, though, are more difficult: Fouls were overturned just 43.9% of the time. The block/charge ranks atop coaches’ list of head scratchers. “Because it’s hard for the referees, too,” says Mahlalela. “Draymond [Green] is the king of it. He’s always looking for [the charge]. And I’m always checking to see if he got all the way over.” Calls involving verticality—whether a defensive player jumps straight up during a collision (which is legal) or is moving forward (which is not)—is another. “Refs can nitpick that one,” says Sears. Shooting fouls, particularly on drives to the basket, can be complicated. “There are usually a lot of bodies in the way,” says Murphy. “You don’t know if another defender had a hand on the hip or if someone else bumped him first.”

In tricky situations, a player becomes a resource. Although not always a reliable one. “We tell our guys, just be honest,” says Bubes. In the NBA, though, nobody thinks they are ever foul. “Pathological liar are not words I’d use,” says Sears, laughing. “But every player thinks they are right.” Challenge guys will track who usually is. “You keep a mental checklist of who has burned you,” says Reynolds. “And who you might owe.” Celtics big man Robert Williams III, says Reynolds, is “very honest.” In Denver, Klask says if Nikola Jokić tells the bench he didn’t commit the foul, “we’re going to go with that.”

Crossing star players occasionally is part of the job. Sears remembers—vividly—a regular-season game against Atlanta, where Dončić pleaded with Mavs coach Jason Kidd to challenge his fifth foul. When Kidd didn’t, Dončić glared at Sears as he headed to the bench. “It’s definitely nerve-racking, when a guy like that gets mad,” says Sears. “But it comes with the territory.”

Three years in, the NBA has deemed its challenge system a success. The numbers have been stable. In the rule’s first season, 2019–20, 633 calls were challenged, with 281 successful, an overturn rate of 44.4%. Last season, 719 calls were challenged, 346 successfully, a 48.1% overturn rate.

To address flow issues at the end of games, the league tweaked the rules last season, taking away referees’ power to review out-of-bounds plays in the final two minutes and overtime, making them reviewable only by a coach’s challenge. That, says NBA president of league operations Byron Spruell, reduced by 60% “outlier games,” which the league defines as those in which the last two minutes take more than 18 minutes of real time. The league has also cracked down on some of the tricks teams have used to buy time—a long shoe tie was a favorite—by slapping delay-of-game warnings and even technical fouls on offenders. “Overall we feel like it’s really been a strategic part of the game that our coaches are truly using,” says Spruell. “Each team I’m sure has its own view of how effective it has been. But we feel like everything’s going in the right direction.”

Challenge guys, for the most part, agree. Sure, it’s stressful. Unsuccessful challenges can bring heat (“If I haven’t won in a couple of games, I might hear about it,” says Murphy), while uncalled ones can result in angry players. Several challenge guys commiserate on a group text, a form of digital therapy. But there’s pride in the position. “Knowing I can impact the game, that’s a cool thing,” says Lumpkin.

And, as with anything else, an eagerness to get better. Some challenge guys have taken to scouting the referee crew chief, noting which are more reluctant to overturn their calls.

Where challenge guys mostly agree: Don’t give us any more of them. A common gripe among head coaches is that they only get one per game. “If they get the first one right,” says Spruell, “they want the ability to use it again.” That has sparked debate inside league offices.

“When I heard that,” says Murphy, “I was like, ‘I’m good.’ One is plenty.” Luckily for Murphy, Spruell says the league needs a few more years of data before it would consider that change.

And while being the challenge guy is a notable position, it’s one many will be thrilled to be promoted out of. “I can’t wait for the day I’m no longer doing this job,” says Sears, smiling. “And I’m going to look back and put just as much pressure on the person behind me.”

More NBA Coverage:

.