You’ve probably heard the apocryphal tale of the frog that lets itself be boiled alive, as long as the water’s heat is turned up slowly. The popular allegory illustrates the way people can accept harmful change, as long as it happens gradually.

Before we break any of that down, I have an important question. Which sickos out there are boiling frogs? Reveal yourselves!

But even if it’s merely a theoretically scientific boiling, I could feel the theoretical frog’s pain, because baseball’s increasingly glacial pace had been cooking me for years.

Worst of all, I knew it — and I couldn’t do anything about it because I had nowhere to jump. There’s no other bat-and-ball sport like baseball. (Mention cricket and I’ll tell you where you can put your googly.)

WELCOME BACK: Tigers bring back infielder Nick Maton after 11 games in Triple-A Toledo

WAIT TILL NEXT YEAR: Tigers 2024 schedule: Opening Day on March 28 at Chicago White Sox

I grew up in Los Angeles with smog, Sig alerts and baseball coursing through my blood. I think I’m Type 0-for-4. A trip to Dodger Stadium meant as much to me as a visit to Disneyland. Future big-leaguers Dave Hansen and Al Martin were a few years ahead of me at my high school. I went to Cal State Fullerton, where I’ve watched future big-leaguers Phil Nevin, Mark Kotsay, Justin Turner, Matt Chapman and Michael Lorenzen.

I loved baseball. But I could feel baseball, in recent years, not loving me back. With every David Ortiz samba dance around the batter’s box, with every Nomar Garciaparra batting-glove performance-art piece, with every Kenley Jansen rain delay between pitches, my love withered.

It was a toxic relationship, yet it owned me. I still watched, especially in the postseason when the stakes were higher and games were even slower. Game 5 of the World Series last year took 3 hours, 57 minutes. It only took John Glenn 58 more minutes to orbit Earth back in 1962. From 2012-22, the average length of an MLB game was at least 3 hours.

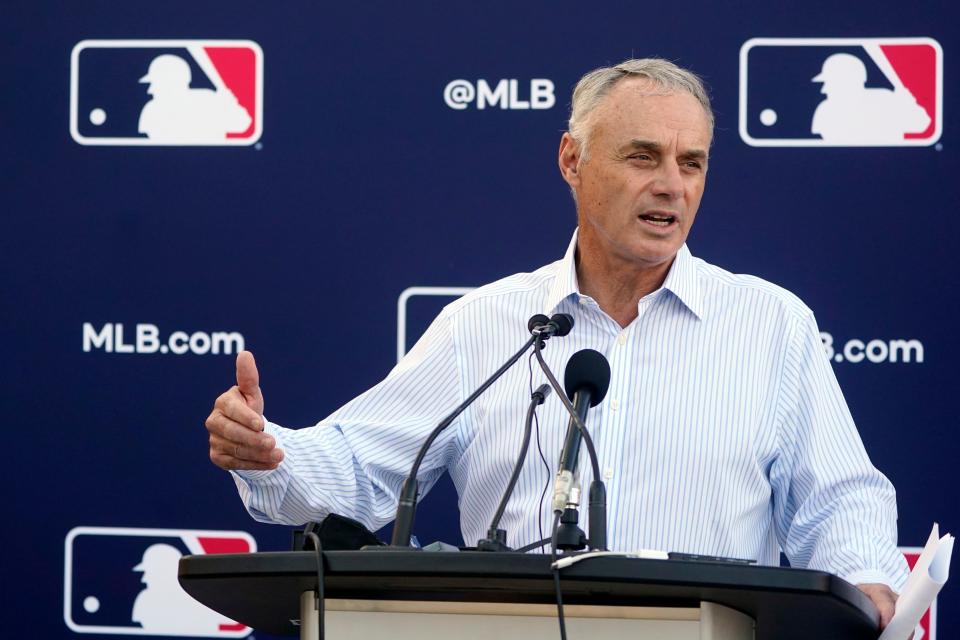

It got so bad that commissioner Rob Manfred quit reviewing daily reports about the length of the previous day’s games.

“Last year was so depressing, I just stopped doing it,” he said in June’s cover story in The Atlantic.

At least Manfred didn’t stop thinking about the problem. A new joint competition committee was formed after a five-year collective-bargaining agreement was signed in March 2022. Just like that, the mechanism was put in place for what is sure to go down as one of baseball’s most drastic changes in 150 years: The pitch clock.

Through half of a season, the results are undeniable.

Average game length last year: 3:06. This year: 2:38.

Runs per game in the first half last year: 4.33. This year: 4.57.

Batting average, homers, RBIs, on-base percentage, stolen bases — you name it, the pitch clock, in conjunction with several other rules changes, has dramatically moved us closer to the “best version of baseball,” a term coined by MLB consultant Theo Epstein, one of the movement’s main architects.

Maybe one of the most telling improved stats is this: 28,236 — MLB’s highest average attendance since 2018, and that’s before we get into late-summer pennant chases and playoff pushes.

Instantly this season, the game I couldn’t bring myself to quit had a whole new hold on me. I no longer felt the need to record games and watch them later in order to whip past all the dead time. In fact, it almost feels now like the game is too fast. A buzz on your phone, a shout from another room, almost any momentary distraction and you’ve missed a pitch or a swing. It’s a small price to pay.

“I think the new rules are exceptionally positive,” Tigers manager AJ Hinch said recently, “really down to all of them.”

Although the rule limiting throws to first, or even steps off the rubber, Hinch admits, is still the most challenging for him.

“But I think they nailed it when it comes to making the game better, faster, more efficient,” he said. “The players have done a really good job of adapting to it. That’s probably my biggest fear was the players weren’t going to buy in.”

Pitchers have been most affected by the new rules, as well as defenses that can no longer shift. At the intersection of the pitching-defense Venn diagram sits the catcher, so it’s understandable that Eric Haase might not be sending Manfred and Epstein an edible arrangement just yet.

“From a catching standpoint, I’m not a big fan of it,” the Tigers backstop said. “You know, I love the faster games and stuff. It’s great in theory.

“But at the same time at this level it takes so much time to cultivate the talent, the work, whatever you want to (call) it. Then you get up here and it’s like, ‘All right, hurry up, we’ve got to play this game.’ And we didn’t grow up learning how to do that. We didn’t develop doing that. So that’s been the biggest challenge.”

Haase hits on an important point. It might take years, if not a generation, for players to fully absorb these rules and consider them second nature.

Lorenzen, the Tigers right-hander and the team’s representative at Tuesday’s All-Star Game, had trouble keeping up with the count early on in spring training because of the clock. He quickly remedied the issue and became a quick convert, which makes a lot of sense for a player who serves a daily role as a de facto dugout cheerleader.

“But I like the rules, 2 ½-hour games,” he said. “It’s always been hard to sit and watch every single game sitting in the dugout. There’s just so much downtime, your mind drifts and you want to come back up in the clubhouse and kind of grab a snack or something.

“But I find myself sitting in the dugout on the bench watching every pitch for the entire game because it’s just, it’s so quick. So I know if I’m able to do that, the fans are definitely able to do that. I’ve enjoyed it.”

Maybe Manfred and Epstein will be the ones ordering that edible arrangement for Lorenzen, thought he did warn about pitchers’ possible fatigue, especially as it gets hotter. Lorenzen tries to buy a little time by not taking the mound too quickly between pitches. Even now, while strikeouts are up, so are walks, and the league ERA has vaulted from 3.99 at last year’s All-Star break to 4.28 entering Friday.

A young player such as Tigers first baseman Spencer Torkelson provides an interesting test case. He’s 23 and hasn’t had as much time to settle into many habits. He’s having a very good second season and said the strictness umpires showed in spring training helped players adapt quickly.

“I think it’s for the better,” he said of the rule changes. “I think fans appreciate it, a little shorter game. We play 162 games, so if you can hit your pillow 30 minutes sooner over the course of a season, that 30 minutes a night is actually a lot of sleep.”

Torkelson touched on a huge unseen benefit for players. Baseball is about projections, and if you cut out 30 minutes a game for an everyday player — who might play 140 games a year — that works out to 70 fewer hours of game time. If games average 2½ hours, that works out to playing 28 fewer games, or at least a rough equivalent of those games, and the wear and tear they create on a player’s body.

Torkelson said he has adjusted to the grind and length of an MLB season, but he can feel the difference even from a year ago.

“My body definitely feels healthier at this point in the season than it did last year at this point in the season,” he said.

Standing at Torkelson’s locker and speaking with him before a game, I noticed his ruddy cheeks and how he speaks with an endearing boyish cheerfulness. He has $8.4 million from his signing bonus as the No. 1 overall pick in 2020, but he still looks like a kid you might hire to mow your lawn or do some odd jobs — complete with a final acknowledgment of “sir.”

I felt an unexpected happiness after Torkelson told me how much he liked the changes. If baseball could finally find a way to become the best version of itself while getting the endorsement from players who are the game’s future, how can you not feel encouraged by that? How can we all not find a way to fall in love with this game all over again?

Contact Carlos Monarrez: [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @cmonarrez.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Instead of breaking up with MLB, I fell in love all over again