San Carlos Island, Florida

CNN

—

There’s an eerie silence inside the Picketts’ living room Wednesday evening as the couple packs up to leave.

The sun is on its way down, and without electricity the narrow, two-bedroom mobile home on San Carlos Island will soon be dark again, lit only dimly by the couple’s few candles.

Next to the front door, 83-year-old Pat Pickett has stacked a small cardboard box on a stool by her open fridge. It’s quickly filling up as she lists out loud to her husband, Leslie, what they’ll need to take with them to the shelter: wash cloths, toothbrushes, a change of clothes. She’s taking a bag of gummy bears, too. The candy helped her quit smoking more than two decades ago and still helps calm her nerves. And, of course, shampoo, for the first shower they’ll take more than a week. She’s excited, she says, to finally get her hair in order.

As they follow each other up and down the hallway at the heart of the house, there is no mention of the chaos around them. Most of the furniture was lifted and tossed by Hurricane Ian’s floodwaters and now lies randomly strewn around the home. An armchair balances on the dining table, a television set sits on its side against the living room wall, portraits of the sea hang crooked. A thin line that’s etched on every wall – about halfway to the ceiling – is a constant reminder of how high the floodwaters reached. On various pieces of furniture, coin-sized patches of bright green mold that sprouted up only get bigger each day.

CDs of Janis Joplin and Dean Martin rest on a muddy rug that covers part of the wood tiling. Loose papers of family recipes are laid out on the surviving tables. The corner kitchen Pat keeps crossing, lit only by a window above the sink, is lined with debris and bowls from the cabinets that she’s tried to empty and dry out. There’s still a lingering stench she hates in there, probably from the chicken and shrimp that went bad when the flood destroyed their fridge. And everything is covered in thick, gray muck, much of which has dried and chipped and turned dusty.

Down their short hallway, Pat grabs a flashlight from the guest bedroom, where the two have spent the past week sleeping. The guest bed floated so high in the flood that its sheets and pillows remained dry and clean, she says. Some of those sheets are now stained with blood, from the gashes Pat and Les sustained on their legs after swimming through the chin-deep waters and wading through the floating furniture.

As they pack their last things, they’re back by the front door. Above the entrance, a custom-made sign reads, “Patience is what the sea teaches.”

“I ran out,” Pat says, responding to the painted phrase.

A week ago, the couple wasn’t sure they would survive. Leslie, 84, loves the nest they’ve created in the Emily Lane mobile home park for the past 18 years, and he didn’t want to leave. And Pat would never leave without him.

But staying was the wrong decision, Leslie admits. When Ian made landfall a little more than 20 miles from their neighborhood, just across the decimated isle of Fort Myers Beach, the canal behind the couple’s porch overflowed and pushed water inside their home. They were freezing as they worked to keep their chins above the water and hurt from the furniture that kept bumping into their small frames. But for five hours, the couple kept swimming, determined to stay alive.

“He said, ‘It’s not our time. God doesn’t want me yet,” Pat says, looking at her husband. “I said, ‘me, neither.’ All we have to do is keep the faith.”

“And that’s what we did,” Leslie says.

“Thank you, God,” his wife adds.

The sun is almost down as the duo slowly walk down the entrance steps to meet Charlie Whitehead, their next-door neighbor, who’ll drive them to a shelter for hurricane evacuees in Estero. The drive is usually about 30 minutes but takes more than an hour since the storm hit because of the broken streetlights.

The three of them didn’t always get along. When the Picketts first bought their home in 2004, Charlie’s three children were still young, and Pat would often catch them playing basketball in the driveway and trampling her bushes. But the Whiteheads and the Picketts have become like family now, she says. “He would help anybody, any time, with anything,” Leslie says.

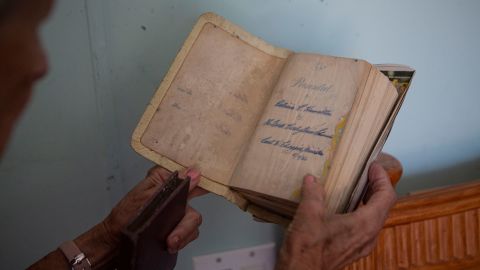

By this time of day, Charlie has turned off the country music he had been playing on a small speaker earlier as he sorted through family pictures on a white glass table outside his home. Much like the Picketts – and most of their neighbors – he wasn’t able to salvage much from the home after the storm. So he’s dedicated his time to saving what can’t be replaced: high school and college diplomas belonging to his children or Debbie, his wife, photographs depicting the first moments after his children were born, graduations, birthdays, hugs with family members who are no longer around.

Charlie has spent much of his life here and knows the Fort Myers Beach community better than most. After moving to join his grandmother in the 1980s, he spent more than two decades reporting for the local paper, was president of the Little League, ran for county commissioner and was twice president of the neighborhood’s association board.

“I have roots in this little mobile home park,” Charlie, 64, says. “Now, I’m just hauling out family pictures, hauling out clothes, trying to save whatever mementos there are.”

He had recently finished thousands of dollars’ worth of fixes after Hurricane Irma wreaked havoc in his home five years ago. Just months ago, he completed a kitchen renovation for Debbie, who liked to spend quiet mornings there.

So he hesitated before leaving his home. But as Ian approached, he decided it wasn’t safe. He urged the Picketts to come with him, but they had made up their minds to stay, he says. When Charlie returned a day later, he phoned his wife, who was visiting family in Colorado, to ask her not to come back. He couldn’t bear her seeing the damage.

“It’s biblical,” he says. “Whether you believe in that stuff or not, what happened here is the kind of stuff you only read about in the Bible.”

But on this evening, there’s little time to think back. The Picketts – after days of refusing to leave their home – have finally agreed to go to a shelter, have a hot meal, take a shower, sleep in a warm bed. He quickly cleans up his red pick-up truck, clearing out the snacks and drinks he had laid out in the back for passersby, and prepares for the drive.

Charlie has been the couple’s only mode of transportation in the past week after their two cars flooded in the storm. He drove the pair to the ER a day after Ian made landfall, when Leslie’s blood pressure spiked. And he spent days trying to convince them to stay in a shelter to get away from the destruction.

The drive doesn’t bother him. In any case, Charlie says, he’s heading in that direction anyway to stay at a friend’s place for the night.

When the sun is back up the following day, Charlie, Pat and Les are right back in position: he’s sorting family pictures and they’re sitting in their lawn chairs by the side of their home, chatting about the chores of the day.

The shelter was not what they had been hoping for. It was packed with other evacuees, many with young children who were anxious and restless, Pat explains. Getting more than four hours of sleep had proved impossible. The long-awaited shower she was looking forward to never came to be, either.

Staff members told them that a rowdy group of people had caused problems in the shower room and had forced the center to close the area until the morning. Before sunrise, Pat called Charlie and told him they were ready to go.

A little after noon on Emily Lane, Charlie brings lunch over to where the pair is sitting: sandwiches in brown paper bags that a friend from Fort Myers Beach had just dropped off.

Next, Pat plans to clean out the bathroom, scrub the floors and pick up the debris so she can take a shower. The duo are also planning to give each other a haircut – a tradition they started decades ago, mostly to save time, when their three sons were young and the pair was working full-time.

Past that, the Picketts have few plans. They’re hoping their youngest son, Tony, can bring a car down from Ohio, so they can go to a doctor’s appointment next week, pick up their mail and go by a local library to meet with FEMA representatives. Without transportation, without power and without internet to fill out the FEMA application online, all they can do now is sit and wait. “And, I’m not a sitter,” says Pat.

“Other than that,” she adds, “life goes on, God’s good, our sons are special.”

“And we don’t expect miracles,” Leslie adds.

That’s as far into the future as their conversations venture these days. Thoughts of rebuilding or moving away don’t seem like a priority yet. “I don’t know what we’re going to do,” Pat had admitted earlier. Although their son has invited them to stay in their home, they both know how harsh Ohio winters can be. Maybe a motor home, she says. Maybe rebuilding, but that will take at least two to three years.

Charlie, who is back clearing through photographs, doesn’t know what’s next either.

“Somebody asked me yesterday what my plans were. And I told them that (at) about dark tonight, I’m going to have a cold beer,” he had said earlier. “There’s not really any way to plan further than that.”

Maybe they’ll move to Colorado with his wife. But Charlie raised three children in the home that sits gutted behind him, and leaving is hard to think about. It’s hard to put into words how he feels and what he’s seen, and he wonders how he’d describe what Ian left behind if he was still a reporter.

“It’s the end of a very long chapter on Fort Myers Beach, on Emily Lane,” he says. “Shit, I don’t know how I would write this story. I’m glad I’m not.”

.