The phone, tablet or laptop you’re reading this on is likely having its battery slowly drained because of a surprising and widespread manufacturing flaw, according to researchers in Halifax.

“This is something that is totally unexpected and something that probably no one thought of,” said Michael Metzger, an assistant professor at Dalhousie University.

The problem? Tiny pieces of tape that hold the battery components together are made from the wrong type of plastic.

Batteries release power because of a chemical reaction. Inside each battery cell, there are two types of metal. One acts as a positive electrode and one as a negative electrode.

These electrodes are held in an electrolyte fluid or paste that is often a form of lithium.

When you connect cables to each end of the battery, electrons flow through the cables – providing power to light bulbs, laptops, or whatever else is on the circuit – and return to the battery.

Trouble starts if those electrons don’t follow the cables.

When electrons move from one charged side of the battery to the other through the electrolyte fluid, it’s called self-discharge. The battery is being depleted internally without sending out electrical current.

This is the reason why devices that are fully charged can slowly lose their charge while they’re turned off.

“These days, batteries are very good,” Metzger said. “But, like with any product, you want it perfected. And you want to eliminate even small rates of self-discharge.”

Stress-testing batteries

In the search for the perfect battery, researchers have to watch how each one performs over its full lifespan.

“We do a lot of our tests at elevated temperatures these days. We want to be able to do testing in reasonable time frames,” Metzger said. Heat makes a battery degrade more quickly, he explained.

At Dalhousie University’s battery lab, dozens of experimental battery cells are being charged and discharged again and again, in environments as hot as 85 C.

For comparison, eggs fry at around 70 C.

If researchers can learn why a battery eventually fails, they can tweak the positive electrode, negative electrode, or electrolyte fluid.

Seeing ed

During one of these tests, the clear electrolyte fluid turned bright red. The team was puzzled.

It isn’t supposed to do that, according to Metzger. “A battery’s a closed system,” he said.

Something new had been created inside the battery.

They did a chemical analysis of the red substance and found it was dimethyl terephthalate (DMT). It’s a substance that shuttles electrons within the battery, rather than having them flow outside through cables and generate electricity.

Shuttling electrons internally depletes the battery’s charge, even if it isn’t connected to a circuit or electrical device.

But if a battery is sealed by the manufacturer, where did the DMT come from?

Through the chemical analysis, the team realized that DMT has a similar structure to another molecule: polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

PET is a type of plastic used in household items like water bottles, food containers and synthetic carpets. But what was plastic doing inside the battery?

Tale of the tape

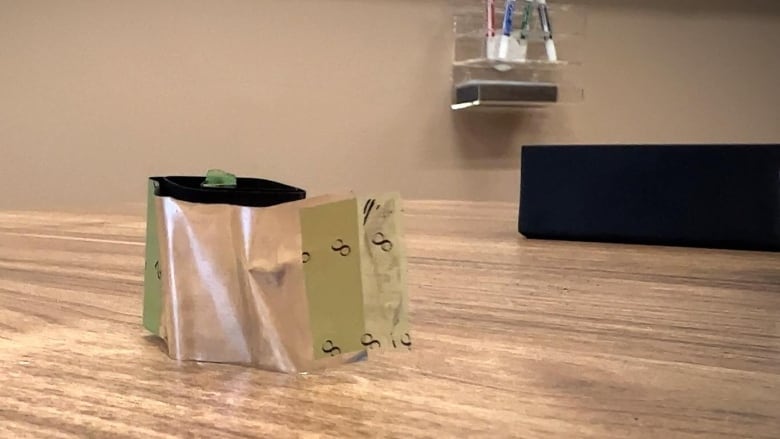

Piece by piece, the team analyzed the battery components. They realized that the thin strips of metal and insulation coiled tightly inside the casing were held together with tape.

Those small segments of tape were made of PET — the type of plastic that had been causing the electrolyte fluid to turn red, and self-discharge the battery.

“A lot of companies use PET tape,” said Metzger. “That’s why it was a quite important discovery, this realization that this tape is actually not inert.”

The tech industry takes notice

Metzger and the team began sharing their discovery publicly in November 2022, in publications and at seminars.

Some of the world’s largest computer-hardware companies and electric-vehicle manufacturers were very interested.

“A lot of the companies made it clear that this is very relevant to them,” Metzger said. “They want to make changes to these components in their battery cells because, of course, they want to avoid self-discharge.”

The team even proposed a solution to the problem: use a slightly more expensive, but also more stable, plastic compound.

One option is polypropylene (PPE), which is typically used to make more durable plastic items like outdoor furniture or reusable water bottles.

“We realized that it [PPE] doesn’t easily decompose like PET, and doesn’t form these unwanted molecules,” Metzger said. “So currently, we have very encouraging results that the self-discharges are truly eliminated by moving away from this PET tape.”