The ACLU and eight federal public defenders are asking the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals to exclude mobile device location data obtained from Google via a so-called geofence warrant that helped law enforcement catch a bank robbery suspect.

The first geofence civil rights case to reach a federal court of appeals raises serious Fourth Amendment concerns against unreasonable search and seizure related to the location and personal information of mobile device users.

Geofence warrants have primarily been issued for Google to hand over data about every cell phone or other mobile device within a specific geographical region and timeframe. The problem: location data on every person carrying a mobile device in that area is scooped up in a wide net and their data is then handed over en masse to law enforcement.

“These warrants are patently unconstitutional,” said Tom McBrien, a law fellow with the nonprofit Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) in Washington DC. “They look through everyone’s location history within that geographical area to see where they were at the time.”

Geofence warrants violate the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution on several fronts, McBrien argued. First, the amendment requires that evidentiary warrants meet the “particularity requirement,” meaning the police must be specific about what and who they’re seeking to find with the data. The warrants can’t turn into “fishing expeditions,” McBrien said.

Secondly, probable cause requires law enforcement to link a specific person or persons to a crime. Only in that case does the law allow the invasion of privacy that comes with geofence data access.

“Google has a rich database of user information,” McBrien said. “You either have a Google phone or you use a Google service. Google has made it very difficult to opt out of location tracking. Even after turning off the specific feature on your mobile phone, Google can still track you through another [service or app]…such as Google Maps.”

Location History is a Google account-level setting that is set to off by default, according to the company. If a device user chooses to turn Location History on, they can still delete parts or all of their location data at any time, or opt to turn it off, according to a Google spokesperson.

Additionally, the first time Location History is activated, Google sends a confirmation email letting users know it is on, along with information about the tool and how to manage it. Users are also reminded in monthly and annual emails that Location History is turned on, Google said.

Google also offers auto-delete controls, that allows users to choose a setting that automatically deletes data on a rolling basis, and it’s the default setting when a user decides to turn Location History on for the first time. Google also offers Incognito Mode in Google Maps, which pauses Location History. When Incognito Mode is activated any web searches or directions are also not saved to a user’s Google account.

Bruce Schneier, a security consultant with Counterpane Systems, said it’s not just Google that has access to geolocation via a cell phone’s ping off a cellular tower. Cellular network providers and cell phone companies also have that data.

“They’re the ones collecting the data and you can’t opt out,” Schneier said, “because that’s how cell phones work.”

McBrien agreed cell phone companies and other network services can track users, but he has yet to see a geofence warrant issued for any company other than Google because it simply has to farm the most data.

“Apple may know where users are, but there are also a lot of Android users not using Apple iPhones — but someone with an iPhone or an Android phone may be using Google Maps,” McBrien said.

From one suspect to thousands?

The problem with geofence warrants goes beyond gaining access to copious amounts of mobile user location data that may, or may not, have anything to do with a crime. Thousands of innocent individuals each year are effectively turned into suspects in criminal investigations through the use of warrants, according to a Harvard Law Review post.

“While traditional court orders permit searches related to known suspects, geofence warrants are issued specifically because a suspect cannot be identified,” the Harvard Law Review noted.

The use of geofence warrants has been snowballing over the past seven years. Since the first one was served on Google in 2016, the number of warrants has increased more than 1,000% every year, according to EPIC.

google

googleThe number of requests from US authorities for user data from Google has grown dramatically over the past few years.

Google received 982 geofence warrants in 2018, 8,396 a year later, and 11,554 in 2020, according to the latest data released by the company. The overwhelming majority of the warrants were issued by courts to state and local law enforcement. Geofence warrants issued to federal authorities amounted to just 4% of those served on Google.

In 2021, Google revealed that one-quarter of all warrants it receives from US authorities — both state and federal — involved geofence requests.

“It’s obvious why these warrants are useful. They have the potential to uncover more suspects,” McBrien said. “I can understand why the courts feel hesitant at first about removing this powerful tool from the police.”

What happens to the date?

While geofence warrants are considered a powerful investigative tool by law enforcement, and the hope is that law enforcement will only use data relevant to their investigation of a crime, there is no way to know for sure, Schneier said.

“The thing about abuses in these instances is they’re hidden,” Schneier said. “If there’s an abuse, you’re not going to know because of parallel construction, which is the way data obtained illegally is washed and not used in court , but data obtained from that data is used.”

For example, the National Security Agency (NSA) might obtain a geofence warrant specific to a suspected criminal, and then pass all of the data to the FBI to let the agency know something suspicious might be happening at a location.

“I’m sure it happens a lot when the NSA passes the FBI data,” Schneier said. “The NSA tells the FBI, ‘This thing is happening on a street corner,’ and the FBI just happens to have an officer there, and the NSA involvement is never mentioned. And, of course, if the FBI has this kind of data, they’re likely to use it for whatever they do [want].”

Last Friday, the ACLU and public defenders released a friend-of-the-court brief requesting mobile device location data obtained from Google to be excluded from evidence, while noting that geolocation warrants are becoming increasingly common.

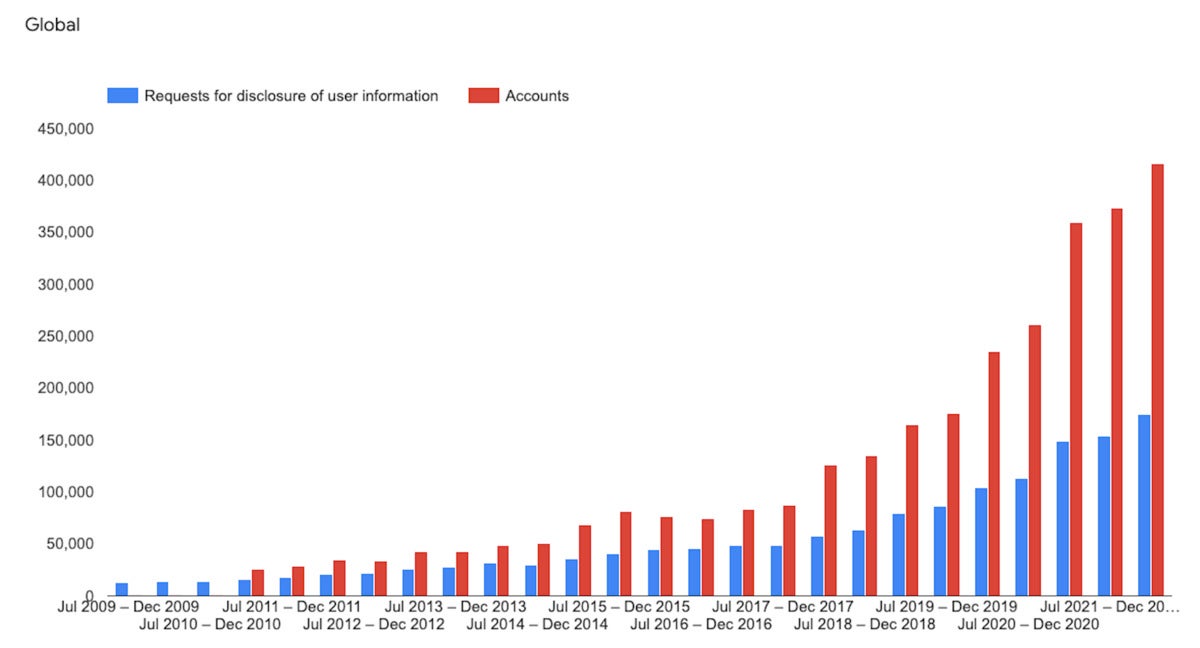

google

googleGlobally, requests for user information from Google have also grown tremendously in recent years.

“They raise serious questions under the Fourth Amendment because they are typically issued without police demonstrating reason to believe all the people who own those devices were involved in any crime,” the ACLU said in a statement.

US vs. Chatrie

The civil rights case in question is United States v. Chatrie. Okello Chatrie, 27, was convicted and sentenced to 12 years in prison using Google Sensorvault data obtained by Virginia law enforcement officials via a geofence warrant. Sensorvault is a Google database that contains records of users’ historical geolocation information.

The appeal came after a federal judge in Virginia held that the geofence warrant in Chatrie’s case was overbroad and lacked probable cause for much of the data police obtained. The warrant sought information about all Google device or app users who were estimated to be within a 17.5-acre area surrounding the location of a bank robbery in Virginia.

“It’s important to note that Google is caught in the middle of this issue,” McBrien said. “We’ve seen examples of Google pushing back on these warrants. Google is saying these look really overly broad — ‘You’re capturing multiple city blocks, including churches, schools and apartments’ — and Google has said this is not passing the smell test.”

In the face of thousands of geofence warrants being served on it every year, Google said its policy has been to scrutinize each one.

“As with all law enforcement demands, we have a rigorous process that is designed to protect the privacy of our users, including by pushing back on overly broad requests, while supporting the important work of law enforcement,” a Google spokesperson wrote in an email respond to Computerworld.

Google also published a “Transparency Report” to answer questions users may have about law enforcement warrants and other user data and privacy issues.

The ACLU spells out its concerns

In the amicus brief, the ACLU and public defenders argued that geofence warrants can incidentally reveal “a wealth of information about the confidential associations of individuals swept up in their net, from a meeting between a journalist and a source to attendance at a church.”

In its statement, the ACLU said law enforcement has seized on the opportunity presented by this “informational stockpile, crafting geofence warrants that seek location data for every user within a particular area.”

There is a relative dearth of case law addressing geofence warrants, according to EPIC’s McBrien. Currently, law enforcement agencies are only held in check by the courts, and they push the envelope whenever they can, he said.

“I’m currently aware of only seven federal cases that have come out [of geofence warrants]. State level cases are harder to track. It’s a new issue,” McBrien said. “There are more coming up every year. There will likely be a lot of case law coming up on this because the use of these warrants is exploding.”

Schneier is not as confident the courts will address the problem quickly and said it’s up to citizens to demand that lawmakers use legislation to limit the reach of geofence warrants. And citizens need to push Congress to address the issue.

“The laws have to be changed,” Schneier said. “There’s no magic thing you can do on your phone to protect it. These are systemic problems that need systemic solutions. So, make this a political issue.”

McBrien believes the courts will eventually catch up with the technology and eventually set limits on the power of companies to collect and distribute geofence data to law enforcement. In the meantime, he agreed with Schneier — a two-pronged approach using both laws and the courts is the best approach to ensure constitutional rights to privacy are upheld.

For example, the New York State legislature is currently considering the Reverse Location Search Prohibition Act, which would prohibit the search, with or without a warrant, of geolocation and keyword data of a group of people who are under no individual suspicion of having committed a crime

“Part of this is society needs to become aware of the problem,” said McBrien.

Copyright © 2023 IDG Communications, Inc.