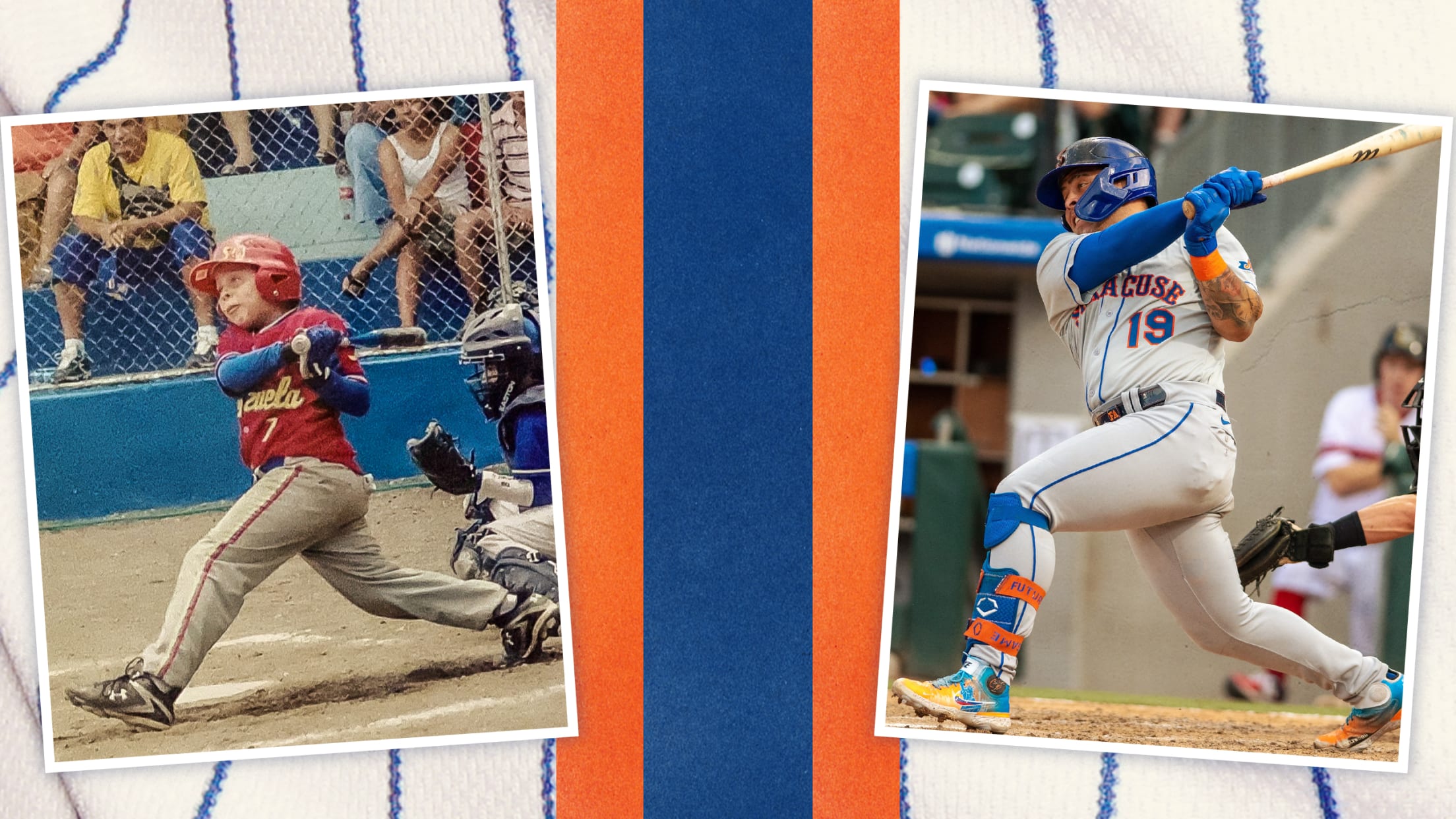

SYRACUSE, NY — Francisco Álvarez is a baseball player, a player. Always has been.

Álvarez’s mother, Yolanda, likes to tell of the time when Álvarez, just 2 or 3 years old, snuck under some netting and wandered onto his older brother’s field in Venezuela. Once there, he found an adult-sized cap and placed it on his head. His family took to calling him “Charlie Brown.”

Yolanda calls Francisco mi toro, Spanish for “my bull.” His father, José, owned a construction company during those days, and Álvarez eventually started helping out, gaining strength by lifting 90-pound concrete bags. As a child, he liked to grab a welder’s shield, snap the plastic down over his face, and pretend he was Major League catcher Henry Blanco, also from Venezuela. With the mask secure, Álvarez would find a bat and beg his grandmother to pitch him kernels of corn.

“He was born to do it,” Yolanda said by telephone from Venezuela.

By age 16, Álvarez was one of the top amateur prospects in the world, signing the largest bonus the Mets had ever paid to an international teenager. By 19, he had become one of the most prodigious power hitters in Minor League Baseball. By 20, Álvarez was on the cusp of the Majors, tantalizing the Mets with his potential as the rare type of catcher who can transform a game with his offense. He was not yet 21 when he became MLB Pipeline’s No. 1 prospect in baseball, and now he is set to make his MLB debut in the final week of a pennant race.

In many ways, Álvarez remains the same mischievous youth he was back in Venezuela, where his family still lives. In others, he is thousands of miles from home.

***

Francisco Álvarez is a hugger, un abrazador. When Álvarez greets people he knows, he likes to clasp their right hand with his own and wrap his left around them. Sometimes, Álvarez will bury his face in the other party’s shoulder and grip tight.

Those close to Álvarez understand what family means to him. Until he was 10 years old, he slept in the same bed with his grandmother, who also shepherded him to baseball practices near his home in Guatire, about an hour east of Caracas. Álvarez’s older sister died as a teenager, and he keeps her memory tattooed on his arm. More ink is dedicated to his mother and father, and to the declaration, “Family first.” That has never changed. Yolanda now works with Álvarez’s dad and older half-brother at a local baseball academy, which the family founded after he signed with the Mets for $2.7 million in 2018. Álvarez trains there for part of the offseason.

“It’s a humble family,” said Ismael Pérez, the area scout who was among the first Mets employees to lay eyes on Álvarez. “It’s what you see in Francisco, too.”

When Álvarez traveled to the United States for his first professional season as a 16-year-old, his parents came along to help ease his transition to a foreign land. The following spring, José and Yolanda were scheduled to join their son again, but the pandemic interfered. Álvarez was invited to the Mets’ alternate training site at Brooklyn, where he competed against players with far more experience. At night, Álvarez frequently fell asleep on the phone with his trainer back in Venezuela.

“I talk to my trainer more than my girlfriend,” Álvarez said with a laugh. “She doesn’t like that.”

Relationships are his lifeblood. About four hours before a recent game at Triple-A Syracuse, Álvarez emerged from the clubhouse and greeted members of the grounds crew in the dugout, shaking each hand in turn. When he realized he had missed an employee who was standing alone by the rail, Alvarez doubled back. The scene evoked memories of his first big league Spring Training, when Álvarez stepped out of the clubhouse, noticed a group of unfamiliar reporters standing nearby, and went over to introduce himself to each one. Álvarez’s hitting coach calls him a teddy bear. His fans up north might use the term mensch.

When Chris Becerra, the Mets’ former international scouting director, initially witnessed this act back in Venezuela, he wondered if it was performance art — the airs of a prospect trying to impress those who could change his life.

“It was like, ‘Who’s this dude? Are you trying to butter me up?’” Becerra recalled. “But that’s just who he is. … I tell people, and it’s not a lie: It’s the best makeup I’ve ever come across in my life. And there have been some good ones. Amed Rosario was a rooster. Andrés Giménez was the quiet, cerebral, super-smart kid.

“[Álvarez] was just like, ‘You want me to bash down a brick wall? I’ll do it right now.’”

***

Francisco Álvarez is a child, un niño , the youngest player at Triple-A for much of his tenure there. He is accustomed to being young.

When Álvarez was 11, he dropped out of traditional schooling to make baseball a full-time pursuit. He had already been on the tournament circuit for years, traveling twice to Nicaragua to participate in games. Álvarez still breaks into a grin as he recalls the time, around age 10, when his mother threatened not to allow him to play in one of those international events because he was misbehaving in school.

That week, when a group of older students knocked on Álvarez’s classroom door, his teacher asked him to let them inside. Shortly thereafter, the students left, and Álvarez — he claims it was the fault of a strong breeze — inadvertently closed the door too hard behind them. The entire class turned and stared. Aware of Álvarez’s reputation as a troublemaker, his teacher believed he slammed it on purpose. The two started arguing. Álvarez received a five-day suspension.

Later that day, he became disconsolate as his mother told him he could no longer attend the tournament in Nicaragua. Álvarez locked himself in his room, sneaking out for bites of food only when he thought no one was looking. Finally, a day before the tournament, Álvarez’s mother told him to pack his bags. He had averted one crisis.

There would be others. About a year later, Álvarez was stewing from an unproductive batting practice session when he began quarreling with his trainer, who had asked him to pick up a stray ball. Álvarez refused. So effusive was the young catcher that his trainer threatened to quit if he didn’t cooperate.

In such dealings, the authority figures in Álvarez’s life always held the trump card: baseball. As long as Álvarez could play, he was happy. So long as he feared losing the game as a punishment, he did his best to stay out of trouble.

These days, Álvarez’s youthful spirit mostly surfaces in innocent ways. He wears mismatched shoelaces on his Jordan sneakers, which he favors in bright colors. When a Syracuse staffer recently took him to Starbucks before a game, he ordered cake pops and macarons and devoured the entire lot. He loves making people laugh. Before another August game, catcher Patrick Mazeika spent some time poking fun at Álvarez’s running style. Mazeika took a few purposely awkward strides around the batting cage, holding his arms at an angle that suggested they were too large to move.

“He runs like he’s six feet wide!” Mazeika said.

“Yeah,” Álvarez snapped back in English. “I’m f—– strong.”

***

Francisco Álvarez is a lion, a lion. A roaring version of the cat, in black ink, stalks its prey on the inside of his left arm. “King of the jungle,” Álvarez explains through an interpreter. “I feel like it’s a motivation for me.”

Frequently, Álvarez draws hopeful comparisons to Mike Piazza: a chiseled, right-handed Hall of Famer who is widely considered the greatest offensive catcher in history. In the batter’s box, Álvarez’s mannerisms are more evocative of Juan Soto, the Nationals-turned-Padres superstar known for his demonstrative at-bats. Like Soto, Álvarez shuffles and shakes as a pitch is delivered, following the path of the baseball with his entire body. His swings are robust. His pace is manic. Seconds after each pitch, he is ready for the next one.

Most stories of Álvarez’s baseball acumen begin with his strength, and rightfully so. It is literal light-tower power; Álvarez banged one off a stanchion in Syracuse during his first month there. A few days after he hit another ball clear out of the stadium in Allentown, Pa., his teammates were still buzzing about the feat. Becerra recalls watching Álvarez “detonating baseballs” as a teenager. He hit 18 homers in 67 games at Binghamton.

When the Mets discovered Álvarez, he was attending a Venezuelan showcase intended for players a full year older than him. It didn’t take more than a few looks for Pérez, the area scout, to believe the kid could become a star.

“When he makes contact, oh boy,” Pérez said. “When you swing at strikes and put it together with eye-hand coordination, bat speed and strength? Forget about it. You’ve got a chance to be special. It’s really hard to find.”

Just as intriguing was Álvarez’s attitude. When scouting teenagers, Pérez likes to ask why they believe the Mets should sign them. The kids typically respond that they want to play professionally, compete in the big leagues, make some money for their families. Álvarez replied that he wanted to become a Hall of Famer and a World Series champion.

“I said, ‘What the f—?'” Pérez recalled, laughing. “This kid is 15 years old, and you’re talking about the Hall of Fame? And making the big leagues in four years? I’ve never seen that mindset before. And from Francisco to now, never again.”

During his scouting assignment, Pérez heard stories about how early Álvarez would begin daily work at the practice field. He made it his mission to beat the kid there. One morning, Pérez arrived at 7 am to find Álvarez already soaked in sweat. Suspicious that the early report time was staged, Pérez stopped alerting Álvarez’s trainer to the days he planned to visit. When Pérez dragged himself to the field at 6 am to find Álvarez already working, he gave up trying to beat him.

These days, Álvarez still reports to the park as early as possible, his afternoons filled with weightlifting, catching drills, batting practice and many other unseen tasks. Upon his promotion to Syracuse, Álvarez immediately stepped into a leadership role, running the team’s pregame pitcher-catcher meetings in both English and Spanish. Every teammate in the room was older than him, some by more than a decade.

“I’ve never believed in being afraid, ever, or of being nervous,” Álvarez said in explanation. “I believe in trying to do things correctly.”

That attitude is why the Mets don’t fret too much over Álvarez’s most obvious limitation: a defensive profile that scouts have questioned since his earliest days as a prospect. If Álvarez can become even an average defender, the Mets know, he’ll provide value in the way that Pete Alonso, who was also considered powerful but defensively challenged as a prospect, has at first base.

Much like a young Alonso, Álvarez features a rare blend of eagerness and confidence. This spring, he generated headlines for saying he hoped to make the Major Leagues in 2022. So emphatic was Álvarez that, when camp broke and the Mets assigned him to Double-A, Álvarez sought out Boles to tell the Triple-A manager: ” I’ll see you soon.”

Four months later, Álvarez was in Syracuse alongside Boles, a step away from the big leagues.

“He knows he’s talented, and he knows what he wants,” Boles said. “But he also has the right attitude and work ethic to get that done.”

.